The global pandemic has pushed educators around the world to a transformative moment for online learning. Since February 2020, an unprecedented number of teachers, students, and parents have become exposed to a new mode of teaching. Teachers did not have the luxury of options, as online education came towards them, shouting “Ready or not, here I come!”

The transformation is deep and wide: All levels of teaching, from pre-k classes to doctoral programs, moved to the cloud. Every discipline, from physics to physical education, from chemistry to creative writing, has a chance to test their limits and potentials in the new modality of teaching.

When people find themselves having to adapt, they can, and they will. Though the change to online teaching did not happen in circumstances that I would prefer, the large-scale experimentation has resulted in booming creativity.

Communities of practices are forming to address common challenges. At the start of the pandemic, teachers shared rapid online teaching resources through Google Docs and listservs. Facebook groups such as “pandemic pedagogy” were created where professors could exchange ideas, tools, methods, suggestions, and also their frustrations.

As teachers become oriented to online teaching, online teaching itself also goes through transformations. I have been an instructional designer since 2005, and some of the assumptions we’ve held dear are facing challenges as a result of technological advancement, cross-pollination of best practices, and new research findings. We may be heading towards online teaching 2.0.

Here are some changes I’ve observed:

| |

Online Teaching 1.0

|

Online Teaching 2.0

|

Teacher

|

- Single teacher as the subject matter expert and course facilitator

|

- Local teacher working with remote teachers, guest speakers, and other resources

- Teaching gigs and uberization of teaching

|

Modality

|

|

- Blending synchronous and asynchronous teaching

- Semester reconfiguration

|

Content

|

|

- Increased use of media

- Interactive content

|

Assessment

|

- Formative assessment

- Summative assessment

|

- Formative assessment

- Summative assessment

- Free-range assessments

|

Interaction

|

- Student-student

- Student-teacher

|

- Student-student

- Student-teacher

- Student-profession

- Student-community

|

Instructional design

|

- Focus on reusable content, modules, and courses

|

- Focus on reusable content, modules, and courses

- Focus on creating rich, unique learning experiences

- Focus on faculty development rather than course development

|

Table: Comparison of Online Teaching 1.0 and 2.0

What are the distinctive trends in the transition from Online Teaching 1.0 to Online Teaching 2.0?

1. Rise of synchronous teaching:

Online teaching prides itself upon the mantra that it can happen anytime, anywhere. Schools discourage teachers from using synchronous teaching methods, on the ground that synchronous teaching may hinder learner flexibility. If a student has a job or is located in a different time zone, it may be difficult to hold a virtual teaching session to gather everyone at the same time.

However, technologies have now made it possible to record and share sessions for those students who are not able to attend live sessions. In this new modality, teachers can blend synchronous and asynchronous online teaching to provide for varied student needs without encouraging absenteeism in their synchronous sessions.

2. Reconfiguration of time:

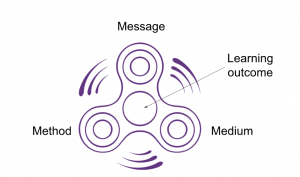

Many schools are already reimagining structured class time to make optimal use of classroom spaces, which may be limited due to social distancing requirements. In this new configuration, courses can be both face-to-face and online, with each modality serving a specific purpose. For instance, lecture videos can be moved online for students to watch themselves, while labs happen face to face. This reconfiguration will depend on the medium (where you teach), method (how you teach), and the message (what you teach).

I envision this future reconfiguration to be like a fidget spinner with three “M”s. When one of them changes, the other two will go through some adjustment as well.

Figure: The Spinner Model Design

The semester schedule may also change. Universities may cancel fall breaks and end semesters on Thanksgiving while devoting the time after Thanksgiving entirely to online teaching. Doing so could reduce travel and the spread of the virus if it continues to be an issue.

However, even after the pandemic is over, it could make sense for such reconfigurations to be institutionalized. Some traditional semester arrangements are based on earlier economies in which a fall break, for instance, was created to allow students to help their families harvest crops. Such traditions have persisted even though the economic norms shifted a long time ago. With new configurations some campus traditions are lost, unfortunately, but other traditions may start to compensate for that loss.

3. Increased use of media:

Online teaching content will increasingly make use of multimedia because it is easy to produce, store, and distribute. Such media may include audio, talking head videos, screencast videos, or screencast videos that include teachers’ talking heads.

Teachers may frown upon talking head videos, but there is an increasing need to add more social presence in an online course. In multiple surveys at my university, students prefer videos that include teachers’ talking heads. This may be a response to a prolonged period of isolation due to the lockdown. Yet even before the pandemic, our students responded well to such videos as they made the courses feel more human.

Interactive content tools like H5P, Genially, Classtools, and Quizlet, which can be used for content review as well as low-stake assessments are becoming more popular.

4. Increase of free-range assignments:

Teachers who are hesitant to use online teaching often cite test security as a major concern. Even with the use of screen-locking applications such as the Lockdown Browser, students may find ways to cheat. But increasingly, teachers realize that they can blend high-stake, standardized tests with more open-ended assessments, including “free-range assignments”. These assignments allow students to demonstrate their mastery of learning in formats they excel at, including papers, videos, presentations, and digital stories.

5. Standardized content with authentic experiences:

Online courses are designed for reusability and replicability. They are often generic, modularized, and de-identified courses that can be assembled in a variety of formations. Some teachers are hired as subject matter experts to produce, often with stipends, courses that can be taught from semester to semester, and in some cases, by different facilitators.

Although this approach has its merits, the increased use of synchronous teaching makes it desirable to project authentic teacher personalities into online courses. Educational institutions may not like this change as authentic experiences are hard to “replicate” or “scale.” However, it creates richer learning experiences and communities of learning for students, which eventually benefit the institutions due to increased social belonging and organizational affiliation. Teachers may embrace this change because personalized components would improve their job security by placing the teacher as central to learning, rather than marginalizing them and making them replaceable.

6. Teaching as a digital performance:

In the past, online teaching reduced teachers to subject matter experts who became invisible once a course is cloned for multiple teachers to use. But in its new iteration, online courses will have profiles and videos of specific teachers that cannot be de-identified.

Instructional media and synchronous sessions require teachers to be more careful of their voice volume, pace of speech, body posture, gesture, dress, and energy. Such requirements can be intimidating! Teachers will always be teachers, but they can make an effort to make themselves presentable, engage in active listening, and display their passion for the subject matter that will spread enthusiasm to their students.

7. Interaction with the community:

Online teaching designers who wanted to promote course interactions, focused on mechanisms that encouraged student-to-content, student-student, and student-teacher interactions, within a closed virtual classroom system. But online teaching since the start of COVID-19 has taught us that it is possible to add another element: student-community interaction.

Teachers became creative with their assignments, and students may have had to tap into their local community resources to complete tasks. For instance, Professor Deonna Shake, a physical education professor at my university, teaches a cycling class, and she asked students to visit a local bike shop to complete an assignment. Previously she would have taught these skills in a classroom.

8. The uberization of teaching:

The ubiquitous use of Zoom has made it possible to include professionals to teach classes. Technically, this has always been possible, but the recent exposure to teaching tools and frequent participation in virtual meetings have more empowered teachers to increase their use of external resources.

The online form of teaching can be liberating. Guest speakers do not have to be in the same city and this opens the door to the uberization of teaching. Platforms like Vipkid have been popular for students who need supplemental instruction, especially in language teaching and learning.

I envision such uberization to increase. In China, for instance, CCTalk has evolved into a big marketplace for teachers and students to learn anything from spoken English to music appreciation. On-demand learning will create opportunities for teachers to have “gigs” as part of their teaching portfolio.

As these trends for online teaching continue to evolve, posing new opportunities and challenges, it is time that educational technologists and instructional designers equip themselves to embrace these changes.